Pella Preservation Trust hosted a living history field trip for all local second grade students for several years. The students come to Tuttle Cabin at 608 Lincoln Street to learn about the life of the first pioneers along with the founding of Pella, Iowa. Because of Covid 19 and social distancing we did not hold the field trip days in 2020 and 2021. The children participate in several centers. These include hearing the story of the Tuttle’s during a fireside chat; Planting and Harvesting; Fun on the Prairie; Sleeping in the Loft; a life of repurposing and making items from objects you already have; and Prairie Chores.

This page may be somewhat advanced for the second grade level, but, hopefully it can be a family activity. Thank you for sharing this history with your families. To print the work sheet; highlight the text and copy to a word document. For the word puzzle; put your mouse on that section, right click and copy image and paste it to a word document. The answers are towards the bottom.

Pella History Worksheet.

- During the 1850’s territory of Iowa the Native American Tribe who were living in Marion County were the __________________________.

Sioux

Apache

Sac and Fox; Mesquakie - This tribe now lives in a settlement called_______________________.

Tama

Waterloo

Des Moines - !843 Pioneers wanted to settle in Iowa to ____________________________.

work in factories

build a homestead with a cabin and farm

go to college - The ________________ built 2 cabins on their homestead claim.

Nosseman’s

Tuttles

Walch’s - ___________________ below the floor of the cabin is where they stored vegetables and fruits. for winter.

Deepfreeze

Cellar

Refrigerator - ___________________ were important animals for milk, cheese, cottage cheese, butters, meat, pulling wagons, plowing fields.

Horses

Cows

Pigs - The Blacksmith made________________________ for the pioneers.

hats

tools

baskets - Pioneers made their own soap from __________________ and Lye.

cotton seed oil

pig fat

tree bark - _________________ was a traveling minister who brought the mail to the settlers in Marion County.

Rev. Moses Post

Rev. Joseph Post

Rev. Wyatt Post - Henry Peter Scholte was born in Amsterdam _________________.

France

Germany

Holland - HP Scholte was called Dominie because he was a __________________.

Reverend

Captain

Professor - The immigrants travelled to America by _____________________.

boat

ship

submarine - The immigrant followers of Scholte travelled by steam ship from St. Louis to ____________ on the way to the land that will become Pella, Iowa.

Pleasantville

Keokuk

Oskaloosa - The Scholte committee that were searching for a place to start their community of Pella met Rev. Post at the __________________ office in Fairfield.

river

valley

land - Pella is between two rivers the Des Moines and the _______________.

Badger

Skunk

Weasel - Because the first homes were dugouts with thatched roofs the settlement was called ________________.

Logtown

Sticktown

Strawtown

Thomas F. and Nancy Jane Tuttle: The Story of two American Pioneers

By Bruce Boertje

In late August 1847 Dominie Scholte led a band of some 400+ Dutch immigrants from St. Louis to the prairie lands of Iowa and founded the town of Pella. But they were not the first settlers to arrive on that spot. Four years earlier, in May 1843, Thomas and Nancy Tuttle “claimed” some of the same land for their farm. One of the first things Scholte did on arrival late that summer was to have the county surveyor lay out the initial nine blocks of Pella – located on top of the Tuttle’s field. Since virgin prairie was not easy to break, the most logical place to begin building a town was in an area that was already cleared. The Tuttle’s field was exactly the right size to hold those first nine blocks – arranged in a three by three grid – of Pella. The center block contained the Tuttle’s log cabin, called a “claim pen”, in what is now Central Park. But who were the Tuttles that broke this prairie, cleared this land and built this cabin?

Thomas F. Tuttle married Nancy Jane Fitzgerald in Fairfield, Iowa in 1842. Thomas, who was 35 at the time, was born in Canada to parents who were both U.S. citizens. While details of Thomas’ early life are unknown, according to Marion County resident and author William Donnell in his 1872 book Pioneers of Marion County, Thomas arrived in the Territory of Iowa in 1838 and moved west to Fairfield the next year. At that time Fairfield had a population of 110 and had just been made the county seat of the newly formed Jefferson County. It was as far west as anyone could legally go in those days – it was literally the end of the American frontier.

Nancy moved to Fairfield in 1842, having been born in Virginia 20 years earlier. On April 12, 1842, Thomas and Nancy applied for a marriage license and were married soon after. It appears that Thomas may have been a widower since the previous census of 1840 listed a female between the age of 20 and 30 in the Tuttle household; but since Nancy didn’t arrive in Iowa until two years later it seems likely that Thomas’ previous wife had died, maybe in childbirth.

The Iowa borders were changing rapidly at that time. Six months after the Tuttles were married, in October 1842, a treaty – commonly referred to as the “New Purchase” – was signed with the Sac and Fox Indians at Agency, IA. This treaty ceded roughly the middle 1/3 of what is today the state of Iowa from the Indians to the U.S. government and gave the Native Americans six months to vacate that area. This territory was then opened to settlers in two stages: the eastern half (whose border was just 10 miles west of Pella) would open on May 1, 1843, and the remainder (on the west side of a north/south dividing line that ran through the Red Rocks that gave name to the former town – and today’s Lake and Dam) on October 11, 1845.

Determined to locate land for a homestead, the Tuttle newlyweds set out from Fairfield as soon as the New Purchase opened. Fairfield and Pella, though approximately 70 miles apart, are located on the same high ridge that separates the Des Moines River from the Skunk River. The Tuttles wandered northwest up that ridge scouting for a suitable location on which to settle. This search took an act of commitment, courage and faith. They loaded as many of their possessions onto a wagon as they could. Since oxen were pulling the wagon travel was slow, especially since there were no roads or bridges – but the views were no doubt spectacular. They enjoyed unlimited prairie covered in tall grass, wild flowers, songbirds, wildlife; groves of timber centered around crystal-clear, tree-lined streams, sloughs and bayous. Once in awhile they probably met – or even traveled with – another adventurous pioneer.

Onboard their wagon was everything needed to start a farm and build a house. Where they were going there were no stores, no doctors, no supplies – or even neighbors – for miles, perhaps for days. After two weeks of searching, on Saturday morning, May 13, 1843 Thomas and Nancy found the spot they were looking for.

Before land in the New Purchase could be sold, the government needed to survey and record it – the pioneers were basically semi-legal squatters. The current practice was to ‘claim’ land: stake it out, build a cabin, break the prairie, farm it and hopefully make enough money to purchase their claim by the time the land was ready for sale.

According to Donnel, the Marion County historian, “Not having any children and no other help, Mrs. T. helped [her husband] to build a cabin in the edge of the nearest timber north of the present site of Pella.” Until this was completed the Tuttles lived outdoors. They cooked over an open fire and slept in or under their wagon – which supplied little in the way of protection from rain, mosquitoes or wolves. Imagine 21-year-old Nancy as she struggled to help Thomas construct their dwelling.

Donnell noted: “The poor settler had neither the means nor the help to erect a palace. The best a settler can do is to fix up the cheapest thing imaginable that could be called a house. Some of the most primitive constructions of the kind were half-faced, or, as they were sometimes called, “cat-faced” sheds.” Donnel went on to say that access to timber was essential to the pioneer. It supplied building materials for shelters and fences, firewood, a measure of protection from prairie fires, while the adjacent ground proved an easier location to plant a vegetable garden before the coming winter. “Soon after this”, continued Donnel, “[the Tuttles] made a claim of part of the [future] town plat of Pella, and put up a claim pen on what is now ‘Garden Square’. …[A] claim cabin was a little more in the shape of a human habitation, made of round logs light enough for two or three men to lay up; about fourteen feet square, roofed with bark or clapboards, and floored with puncheons (logs split into slabs), or earth. …This cabin remained there, and was for a portion of the time occupied several years after the city had grown up around it.” Indeed, Tuttle’s cabin stood in Central Park for nearly 20 years and became the Scholte’s first home when they arrived in Pella.

In addition to claiming land and erecting shelter, a well had to be dug, food had to be gathered, game had to be hunted and most important, the prairie had to be broken so that crops could be planted the following year. Marion County pioneer Alfred McCown recalled the prairie-busting process in his book Down on the Ridge: “To wrest this new home from nature’s lap meant many weary days of toil and sacrifice. There were rails to split and haul, fences to build, brush to grub out of the ground, hazel thickets to cut down and the brush to pile and burn, and then the unlocking of the virgin soil. This breaking of the soil and hauling they did with cattle. The fertile soil they turned over with a huge breaking plow with massive beam to which were hitched [a] yoke of oxen, turning over with the soil myriads of hazel roots in great clusters.”

Fortunately it was summer and the days were long. Work continued from sun-up to sundown. Donnel related, rather matter-of-factly: “After being here a month or so it was found necessary to replenish their stock of breadstuff ere it should run too low; so it was decided to go to Fort Madison for a supply, Mrs. T to accompany her husband or to stay at home as she chose.” In order to obtain grain – to feed both themselves and their oxen – Thomas set out on an arduous nine-day trip to purchase grain and have it ground. Nancy courageously remained behind to guard their claim and their few possessions; there were still some Indians roaming the territory.

Donnel recorded: “When this lonely pair took up their residence in the county they were not aware of the existence of another family of white people within twenty miles of them.” However, this was not really the case. Prior to the Tuttles arrival, a group of five pioneers had considered settling on the area of the Tuttle’s future claim. Instead they selected land about three miles south of Pella, not far from the Des Moines River, due to its proximity to more abundant timberlands.

About the time that Thomas returned from his trip to Fort Madison, federal surveyor William Burt began an initial survey of the future Marion County area. This was a very high-level survey, its purpose was to simply mark and document geographic townships. Many Iowa counties consist of 16 geographic townships, each one consisting of 36 square miles. A side note on Burt: In addition to traipsing through the wilderness as a surveyor, he was known for inventing and patenting the first typewriter and a solar compass. The latter vastly improved surveying accuracy.

In late August four Buffington brothers and their families claimed land about three miles north of the Tuttles. By the end of that first year approximately 70 pioneering families had settled in the eastern half of the future Marion County. This may sound like a lot, but it was only an average of one family per four square miles.

As if the challenges of that first year weren’t enough Donnell tells us that, “The winter of 1843-4 was one of great severity and length followed by a late spring. The Des Moines River remained closed till the middle of April; then, about the last of May heavy rains began and continued till the middle of July, so that what could be planted was but indifferently cultivated. Finally came a keen September frost that cut short what was already much curtailed by late planting and poor cultivation. Some wheat had been sown, but it not only yielded poorly, but was more or less effected by rust and smut.” Due to the weather, grain and produce remained scarce for a second year. Fortunately the next winter, 1844-5, was as mild as the prior winter had been long and severe. At last an abundant crop was produced, and combined with the opening of a mill on the Skunk River north of Oskaloosa, lengthy trips to grind grain came to an end.

In August 1845 Marion County was officially organized. A comprehensive survey of the eastern part of the county – which includes Pella and its surrounding area – was begun. This survey is significant in that it showed – for the first time – the location of the Tuttle’s farm field, which ultimately became the location for the center of Pella. In 1846 the county’s communication to the outside world was established with the opening of a mail route to Knoxville. On December 28 Iowa gave up its status as a territory when it was admitted to the Union as the 29th state.

In late May 1847 Dominie Scholte and the Dutch colonists arrived in the United States seeking religious and economic freedom. They painstakingly made their way across the country, arriving in St. Louis by the first of July, in search of a location for their settlement. Approximately 900 colonists had emigrated from the Netherlands, but only about 800 ultimately survived the long and arduous trip to Pella.

While the Hollanders recuperated in St. Louis, a band of five men, including Scholte, made their way to Iowa to scout for settlement locations. They found themselves in the land office in Fairfield – the same town in which the Tuttle’s were married and departed for the New Purchase. While there, Scholte chanced to meet fellow minister Rev. Moses Post at a funeral for the daughter of the local land agent. Post was an itinerant Baptist minister and missionary who had extensive knowledge of south-eastern Iowa. In addition to bringing the gospel, Post had also recently begun carrying mail via the grandly named “State Road” – which at that time was barely a path that ran through the wilderness between Fairfield and Fort Des Moines. Coincidentally, the State Road also ran alongside the Tuttle’s farm. After introductions, Rev. Post informed Scholte that he knew of a few suitable locations for a community.

“Once having noted the hand of God [in meeting Rev. Post] I did not let loose,” Scholte recalled, “and after speaking with the other members of the Committee who shared my conviction I persuaded [Rev. Post] … that we would set out the following day. This we did, and by Thursday noon we were at the place where I now write”. (By this time Scholte was living in the former Tuttle log cabin, now located in the center of Pella!) Scholte and the scouting party immediately set about purchasing the claims of as many settlers in the area as they could.

“We began straightway with the man at whose house we had dinner at noon,” Scholte wrote, “and with him agreed upon the price of his farm, reserving the right to give him a definite answer not later than one o’clock Saturday, because we wanted to be assured of the other farms first. He gave us a short list of the various settlers, and by constant riding, before darkness set in, we had everybody’s promise to sell at a stipulated price.” A second day was spent acquiring claims from settlers living closer to the Des Moines River, but that was all it took to garner the necessary land.

Most of the settlers readily accepted Scholte’s offer. Subsistence farming was the norm since there were no ready markets in which to sell crops or livestock and thus make a profit. Money was exceedingly scarce. The fact that so many settlers jumped at Scholte’s offer to purchase their land (in gold) so late in the year demonstrates how desperate they were for money. Scholte signed agreements to purchase the settlers’ land in July and later wrote that in the “latter half of August I paid off those settlers and took possession of [their] claims”.

Government land nominally sold for $1.25 an acre. Scholte offered this same amount to the settlers for their claims – usually paying more for land that came with crops, livestock or a dwelling. The drawback was that when the land officially came up for sale the next year, Scholte had to turn around and purchase the claimed land again, this time from the government.

In mid-August Scholte and a majority (Scholte termed it “over half”) of his 800+ wandering Hollanders left St. Louis to complete the final leg of their journey. The remainder wintered in St. Louis before sporadically arriving in Pella the next spring. With the arrival of the Dutch colony and the completed sale of their claim, the Tuttles once again headed up the ridge dividing the Des Moines and Skunk rivers. This time Thomas and Nancy’s trip was shorter – about 20 miles. They found a location in southwestern Jasper County near what became Vandalia, a small community south of Prairie City. Since it was already September and the Tuttles now had some money to spend, it is likely that they purchased an existing farm.

Three years later the Tuttle’s had a thriving farm, as indicated by the 1850 census. According to official records Thomas and Nancy owned a total of 130 acres of land: 50 acres improved (i.e. cleared land) and 80 acres unimproved. The cash value of their farm was $300. They had $20 worth of farming implements, 2 horses, 5 milk cows, 2 working oxen, 5 other cattle and 40 swine for a total livestock value of $200. They also had 600 bushels of ‘Indian’ corn, 5 bushels of peas and beans, 50 bushels of potatoes and 750 pounds of butter; two tons of hay and 200 pounds of beeswax and honey. Their total value of animals slaughtered that year was $100. In addition, the census listed 17-year-old John Anderson as living with the Tuttles. He was probably a hired hand helping to work the farm. Scholte’s money had aided the Tuttles in building their farm, but this inventory also gives some insight as to what the Tuttles left behind on the farm they sold to Scholte.

Thomas, still legally a Canadian citizen, applied for and received U.S. citizenship in 1851. Their pioneering days over, Thomas and Nancy settled down and continued to farm for many years. The 1856 census provided a picture of tranquility: Nancy kept house while Thomas farmed. By 1860 the Tuttles had increased their land holdings to 200 acres, which included 70 acres of improved land. Their farm machinery value more than tripled to $100 and their inventory now included 500 gallons of molasses. By 1870 they were still farming and 12-year-old Edith Swallow, born in Indiana, lived with them while she attended school.

With the advancing years, Thomas eventually gave up the farm, and by 1878 he and Nancy were retired and living in Prairie City. The last mention of the Tuttles was in the 1880 census when they were listed as boarders on Jefferson Street in Prairie City – Thomas was 72 and Nancy was 57. It is likely that the Tuttles passed their remaining years in Prairie City and now lie buried somewhere nearby – although no records have been found to confirm this.

Thus ends the story of two daring and courageous American pioneers. They braved – and broke – the wild prairie. They may not have reared any children, but they left two thriving farms – and one small city – as their legacy.

(below are also answers to above questions, not in order)

CELLAR

COWS

FARM

HOLLAND

KEOKUK

LAND

MESQUAKIE

MOSES

PIGFAT

REVEREND

SHIP

SKUNK

STRAWTOWN

TAMA

TOOLS

TUTTLES

How to Play Marbles

Set up 13 glass or clay marbles in a cross shape at the center of a circle or ring. If you’re outside you can draw a circle in the dirt, or with chalk on a hard surface. If you are inside you can make a circle with tape or string. Traditionally the game calls for a ring or circle ten feet in diameter, but if you are a beginner, we suggest something smaller – perhaps four or five feet.

Players take turns with their “shooters” (larger marbles) trying to knock one or more of the marbles out of the ring. They must shoot from outside the ring (hands and all body parts must be outside), but you can shoot from anywhere outside the ring. If, when shooting you knock it out of the ring, and your shooter stays in the ring, you may take another shot and you win the marble. You may take your next shot from inside the ring from the point your shooter came to rest. If you keep knocking marbles out of the ring and your shooter stays in the ring you may keep shooting. If you strike a marble and knock it out of the ring, but your shooter also goes out of the ring, you “win” the marble but your turn is over. If you strike a marble but do not knock it out of the ring, and your shooter stays inside the ring you do not win any marbles and your turn is over; your shooter must stay where it came to rest until your next turn.

If you strike a marble but do not knock it out of the ring, but your shooter leaves the ring, your turn is over but you can pick up your shooter; on your next turn you can shoot from anywhere outside the circle

If your opponent’s shooter is left inside the circle, and his or her turn is over, then on your turn you may elect to try to knock it out of the circle rather than shooting at a marble; if you manage to knock your opponent’s shooter out you win all of the marbles that he or she has gathered to that point.

The game ends when all of the 13 marbles have been knocked out of the circle; the player with the most marbles at that point is the winner. We play the game for points, some play that the winner keeps the other players marbles!

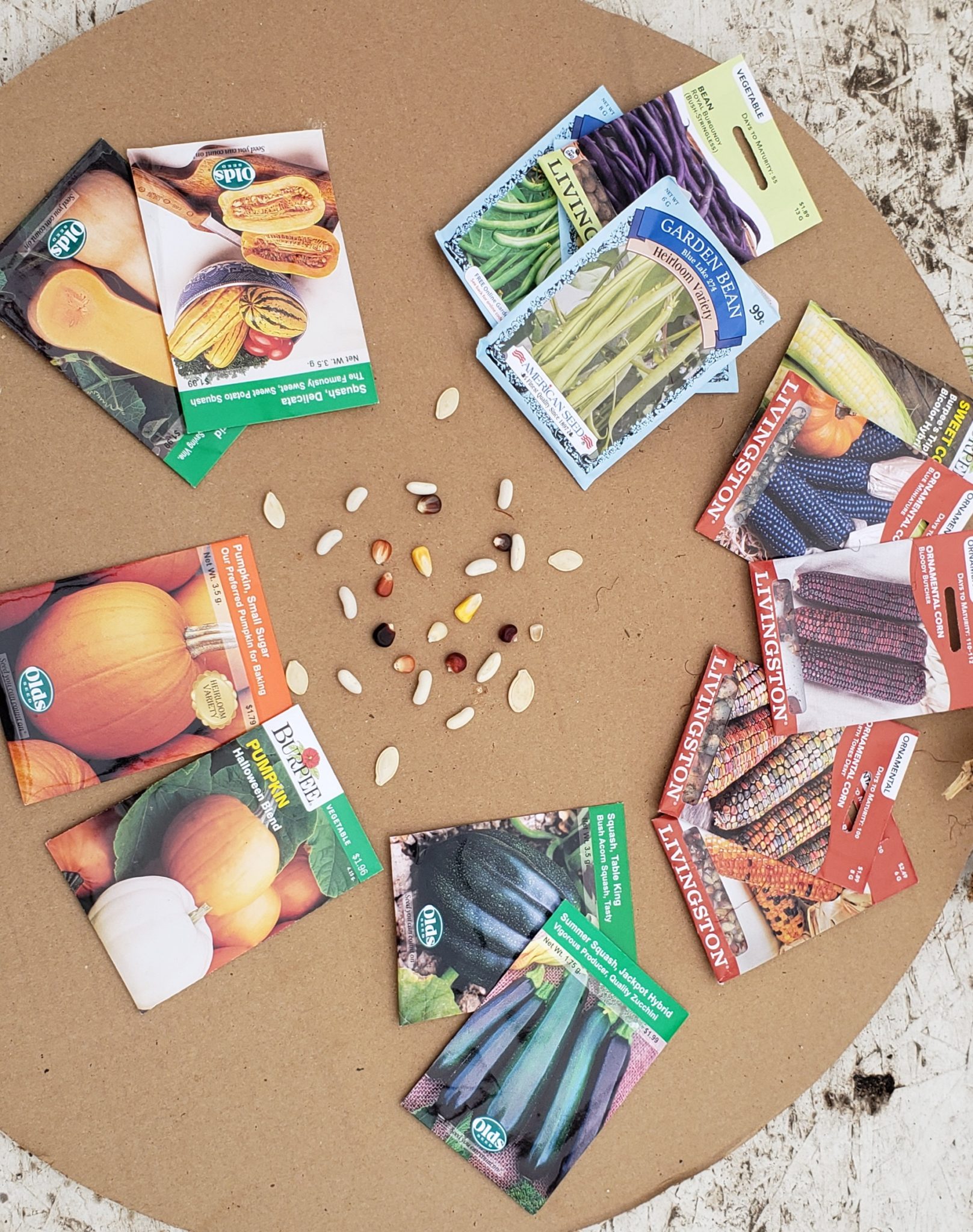

The Native American Three Sisters Planting Method

Build a circular mound of soil about 5 feet in diameter, raking the top of it into a flat planting area with tapered sides (the finished bed should be at least 6 inches tall). Mix compost and soil amendments into the soil as needed.

Plant the corn first so it gets a head start. Sow the seed eight inches apart in a 3-foot diameter circle on top of the bed.

Once the cornstalks are 6 to 8 inches tall, plant the bean and squash seeds. The bean seeds go inside the circle of corn, with one seed planted about 3 inches from each cornstalk. The squash seeds go outside the circle of corn near the edge of the bed; the seeds should be about 12 inches from the closest cornstalks, but space these widely, with about 24 inches between each.

As the bean vines grow, direct them toward the nearest cornstalk; you can tie them to the stalk with a piece of twine to ensure they clamber upwards, rather than along the ground.

Build as many circular mounds as you like, but leave plenty of space between each one, as the squash will quickly spread beyond its bed to cover an area roughly 10 feet in diameter.

Keep the beds watered and weeded as needed.

The beans and corn will mature first. Step carefully among the squash vines to harvest them as they ripen.